- Prepping, liming and seeding 4 acres of pasture

- Build a 4 x 6 root cellar (meat/cheese aging cave) in basement

- Move a door in the garage for easier hay access

- Build a mud room to keep the house cleaner

- Replace sink in basement and possibly install a stove for cheese making

- Jack up the chicken coop and rebuild the foundation which is failing

- Reside and reroof the chicken coop

- Build the permanent goat paddock fence

- Dig up the underperforming drainage lines and replace with larger pipes across entire length of the property

- Plant an orchard

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

A Day In The Life

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

The Taming Of The Shrew

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Winter Greens

It's mid-January and for the Northern Hemisphere, that means winter. Lots of people are deep in the throes of winter blues, but I'm feeling a bit... "green" this year. Winter greens... mmmm... delicious.

Some of the tastiest plants like it cold and do well in near freezing (and sometimes below freezing) temps. Since this was the first winter with the greenhouse, I decided to try my hand at winter gardening.

Over the summer, I read and re-read Eliot Coleman's Four Season Harvest. The man is inspiring for many reasons, but a big one is that he lives up the road from me in Maine. He's more northern than I but is right on the coast, so has some advantage there. However, in page after page of his book, he makes a compelling case for selecting and growing cold-weather crops. Heating a greenhouse through the winter takes energy and is wasteful. But if you work with the plants that love the cold, you can have fresh greens without any extra electricity. Sounds right up my alley.

In keeping with the theme of "At Least I am Learning", not everything went according to plan. For one, Coleman recommends starting your winter veggies in August at my latitude. In August, I was suffering from heat exhaustion and the last thing I was thinking about was winter. I thought if I planted my greens now, they would mature and bolt by the time it got cold enough to put them in a deep sleep for the winter. So I stalled.

And stalled.

And then, at the beginning of October, I remembered and feverishly planted. My poor lettuces and kale. They tried to grow as fast as they could, but the sun was already low in the southern sky and it was cold at night. I completely underestimated how up here it goes from late summer to late fall in two weeks and that the lack of sun was the biggest problem.

But the wee plants did their best and I was able to prove that even now, in mid January, green things are not dead in my greenhouse despite the lack of heat and the extra cold this year.

Snowy greenhouse (and cute goats).

Snowy greenhouse (and cute goats).

I ended up growing two sets of plants, those under an internal cold frame and those outside a cold frame. I wanted a "Control Group" for this experiment. I wondered if the double layer of plastic in the cold frame would slow down the meager sunlight and stunt the plants. The opposite effect occurred. The plants under the cold frame far surpassed those outside the cold frame, although both sets survived and did not die from frost. Totally fascinating.

Double layers. A cold frame within the greenhouse.

Double layers. A cold frame within the greenhouse.

Plants under the cold frame doing much better.

Plants under the cold frame doing much better.

Looking good, just not big enough.

Looking good, just not big enough.

Overall, I am very pleased and I am planning to keep a bunch of those plants through the winter for my early start in spring greens since they will likely grow as soon as things warm up. The biggest problem is I didn't plant enough greens and didn't let them grow enough before the seasons changed. Both issues are easy to fix next year and I can't wait to see how much greener I am in January 2011!

Friday, January 15, 2010

2009 Seed Swap Update!

Sunday, January 10, 2010

What Do I Get With 5.5 Acres?

My small farm is only 5.5 acres. That's "micro" scale as far as farms go. And to add insult to injury, when I bought it, it was 80% wooded.

When I decided to move to New England, I had fantasies of the old white farmhouses, the big grass fields, the stone walls. I was hoping for 30 acres, all arable, with a 5 stall barn to boot. Well, nothing makes you feel poor like shopping for farms in New England. That 30 acre farm I just described would be a cool million anywhere commutable to Portsmouth (the location of my job at the time). You could find that kind of acreage for cheaper, but it would not be arable, much less pastured. We're talking swamp, people.

Anyway, after nine months of searching for a farm, I found this little parcel and the house was nice, so I went for it. Five acres and change is a far cry from my romantic New England homestead, but we all have to start somewhere. It might as well be at the bottom.

I moved in on November 1, 2008, just beating winter by a mere few weeks. My first introduction to hard farm life was an ice storm on December 18th that left us without power for five days. No heat, no water, no electric fence for the horses. We learned from that one and now have a generator and a healthy appreciation and respect for winter.

The following year, 2009, we barely got our feet under us. We fenced off a small 3/4 acre paddock for the horses out in the woods, got some chickens, and tilled up the sod on a 40' diameter garden disc aka our leach field. It was a terrible year for weather, but a good year for learning. I watched how the sun rose and set on the farm, where the shadows lay in each season, where the wind would bite the coldest. I learned a lot about the natural rhythm of the spring which feeds our livestock trough. I learned more than I wanted about flood drainage and how even though it is tough to be on the side of a steep hill, it's worse to be at the bottom. Maybe we didn't start at the bottom, after all.

2009 Farm. Satellite photo from 2007 but this is how the property looked when purchased. Improvements in red.

2009 Farm. Satellite photo from 2007 but this is how the property looked when purchased. Improvements in red.

Anyway, the bad news is that we will now get stumped on May 1, 2010, because that's how long it will take after mud season to get the big machines back in. The good news is that we got more money for the wood they cleared than we thought, so we just might be able to afford all these "improvements". So pastures in (late) 2010 and, with luck, we will get to graze them in 2011.

As for the rest of the property, the front 1/2 acre was cleared save for some truly awesome old oaks. It will be used for an orchard and a meadow grazed on a 150 day management cycle. The goats will get a 100' x 45' permanently fenced paddock (once the ground thaws), and I have portable electric fencing to graze them out during the day. The garden will be expanded to approximately twice the square footage. And we will see how that goes.

A note on the pictures. The green dots roughly represent large trees, but we saved more trees than it looks like from that representation. I want living pasture, not strip-cleared dead zones. In addition, we have plans to plant approximately 20 fruit and nut trees in the orchard and other areas of the farm.

Future pasture from future goat paddock. Plenty of gorgeous trees and now hopefully more gorgeous sun.

Future pasture from future goat paddock. Plenty of gorgeous trees and now hopefully more gorgeous sun.

What is becoming very obvious from our experience is that even though the farm is micro-scaled, we could very easily produce almost all the food we need IF we did not have the horses. The horses will take up 3.5 acres of land and they would destroy it if not managed properly. I could raise 30 goats or 10 pigs or 20 sheep on the same amount of land and have a much easier time keeping it healthy. But the horses are here to stay, because there's more to life than farming and that's being loved by a goofy draft horse.

Micro-farms are very viable, however, if properly managed. So although I still wax poetic about my "next" 30 acre farm, that's just so I can have more horses. Or goats. :)

Why Lard?

I had a couple of readers ask about the purpose of lard and how we would use it. I thought the answer was so obvious, I failed to put in the previous post. We would use lard for cooking!

Ah, but there's more to it than that. Lard historically has been used where we now use butter or other vegetable oils. Despite its somewhat nasty reputation, lard has less saturated fat, more unsaturated fat, and less cholesterol than butter. And, unlike margarine or shortening, lard contains no trans fat.

I don't happen to live in Iowa or, tragically, Italy, so corn and olive oils are not local foods. Nor do they provide the right kind of "mouthfeel" for moist but flakey baked goods. Lard also has a relatively high smoke point, producing little smoke when heated and is more stable at higher temperatures. To read all about lard, check out the wikipedia article for more benefits for cooking.

Of special note is that the kind of back fat I showed in the pictures does not come from modern pork pigs. You need a heritage pig bred to create fat (which most of our fat phobic dieters abhor) and it needs to live outside to be stimulated to produce more than 1" of fat under the skin. Our pig was a Tamworth x Berkshire.

As for our uses, we will use small amounts of lard for frying up meats so they don't stick to the pan. We will make tortillas and pie crusts, including quiche. We recently used it to grease a pan for bread pudding, using up old, stale homemade bread. Basically, we will use lard for anything we would use oil for if the food combines well with a more "savory" fat.

Once my goats are in production and I am making homemade butter, the hope is to limit our olive oil use to just what is required, such as marinating mozzarella (which, in my opinion is a "need" and not a "want"). Olive oil, like tea and coffee, are not produced locally so will figure into the 30% we allow ourselves to come outside of our sphere of influence.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

The Goodness of Lard

Lard has been much maligned recently, but I think with the "Trans Fat" scare, people are starting to realize that animal fats aren't really all that bad. On a scale between Good and Evil, lard is not exactly lily-white Luke Skywalker. It's more of the Han Solo type (after all, Han did shoot Greedo first). You can't help but love it and nibble it all over. Lard, that is. Not Han. Ok, well maybe Han a little.

Anyway, lard contains about 40% saturated fat and 45% monosaturated fat. For reference, coconut and palm kernal oil run 80% in saturated fat. It is also high in Omega 6 fatty acids, Vitamin D and has some nice anti-bacterial properties as well. There's a reason soap has traditionally been made from animal fats and don't even think about hanging that nice slab of beef for three weeks unless there is a nice layer of fat covering it.

But don't run out and buy a tub o' lard for your next cookoff. The lard from the store has been hydrogenated to increase shelf life. And like most things done for preservation, injecting the lard with Hyrdrogen negates a lot of the good benefits, leaving the fact that it is just a bunch of fat. The best and healthiest way to use lard is to render it yourself from pig fat from a local farmer.

You knew I was going to say that, didn't you.

This year, we bought a whole pig from a local farmer. What that means is that we purchased a pig and even though the farmer raised the pig and delivered him to the butcher, he was technically our pig. We paid the farmer for the pig and the butcher for the processing and got the added benefit of being able to specify what we wanted back in little packages. Because we don't believe in wasting anything from an animal, we got it ALL back. So we received about 154 lbs of pig parts, including the head and trotters. About 120 lbs of that pork were prime cuts, ham, and bacon. Not a bad deal.

In case you are wondering, the head is great for jowl bacon and tamales and some amazing stock. Waste not, want not!

But today is all about the lard. As part of our pig, we received about 20 lbs of back fat and leaf fat. For lard aficionados, leaf fat, the fat from around the kidneys, is preferred because it can be rendered "purer" with less porky flavor. Another tip for less porky flavor is to not overcook it. If you heat the fat until the cracklins turn brown, it's too late and you get a more "savory" lard.

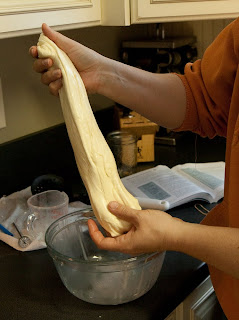

We cooked our lard via the "wet" method, where we poured the hot oil into water to allow the water to bring the stray proteins out. Then you reheat the water/oil mix until you stop hearing any sizzling. At that point, all the water has evaporated out, and the oil you pour off cools to a snow-white finish. Yum!

The cracklins can be saved to flavor meat soups and to feed to the chickens on cold days where lots of calories will help them stay warm.

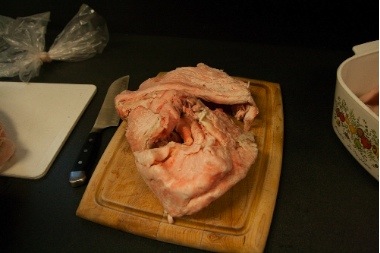

The bag of fat as delivered from the butcher

The bag of fat as delivered from the butcher

The bag opened. Leaf fat is hiding under the first slab of back fat.

The bag opened. Leaf fat is hiding under the first slab of back fat.

Back fat being cubed. The smaller the cubes, the more yield. Also, it's easiest to cut the fat when it is semi-frozen.

Back fat being cubed. The smaller the cubes, the more yield. Also, it's easiest to cut the fat when it is semi-frozen.

A slab o' fat makes lots of cubes.

A slab o' fat makes lots of cubes.

Two pans of fat ready to go. Leaf fat is on the left, back fat on the right.

Two pans of fat ready to go. Leaf fat is on the left, back fat on the right.

Pouring the oil into a pot of water, filtering out the cracklins and solids.

Pouring the oil into a pot of water, filtering out the cracklins and solids.

We cooled our lard with snow, the traditional method!!

We cooled our lard with snow, the traditional method!!

The finished product. We used less than half our fat to make this much lard.

The finished product. We used less than half our fat to make this much lard.

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

An Exercise in Futility

But sometimes, I can't help myself. Sometimes, I just rant. I am feeling that urge again. I broke down and watched Food, Inc (I linked to it on PBS, because you can watch it for free starting in April) the other night. I told myself I didn't need to watch it, I already knew most of what was said. I had heard of it, of course, and how good it was, so I finally caved. And I have been in a clinical depression since.

The scale of the problem is simply overwhelming. One single processing plant slaughters 32,000 terrified, screaming pigs A DAY. The downer cows, cruelly tortured to get them to their feet for slaughter, number in the hundreds PER DAY. And the corruption and lies go all the way to the top, from former Monsanto employees holding positions in the USDA and other conflicts of interest. Who polices the police??? What can one woman do against such reckless hate? And it is hate; hatred for the animals, hatred for the customers who die from e-coli contaminated food, hatred for our humanity which has been stripped away from something as vital and base as our food.

The answer to the question of what one woman can do is answered in the movie: Nothing. My withdrawing from the industrial food supply will probably mean better health for me and my family and more dollars to local farmers (all good things), but we're not the ones driving the cruelty in the slaughterhouses anyway. We've already opted out. The people who shop at Walmart are making the difference. Walmart starting carrying Organic products because consumers demanded it, not because they thought it was a Nice Thing to do. Organics are a mixed bag, but at least they are not GMO and use fewer pesticides in their production. The shoppers of Walmart took THOUSANDS OF TONS of poison out of the environment. Kind of staggering to think about, isn't it?

The lesson is clear: If we, collectively, demand cleaner food, the big businesses will deliver. Despite my pastoral dreams, the world is not going to change so that each family can have a couple of hens and a goat in the back yard. Our economy *needs* us to be workers, not farmers. We need 8-12 productive hours a day doing "work", not growing our own food, to keep our insatiable economy going. People are not going to give up their satellite TV money (apparently) to eat "Slow Food". Big business will remain in the picture, but if we can change Big Business, we can change things on a colossal scale.

You know, I was wrong, I did learn quite a bit from Food, Inc. One of the things I learned was about the treatment of hamburger with Ammonia to "cleanse" it from salmonella and e-coli. I have already discussed the ubiquitous practice of bleaching chicken. Now the NY Time is running an article about our favorite little magic meat machine, Beef Products Inc. It's a good, if scary read, and speaks to the

If you are still reading this, thank you. I will tantalize you with a promise that my next post will be about rendering the lard from our pig. Exciting stuff!!

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Cheese At Home